Lauren Lynch Novakovic of Knoxville hands out signs to demonstrators prior to the hearing on inclusionary zoning in the City-County Building on Sept. 10, 2025. More than 25 demonstrators gathered Downtown to express their support for “IZ” prior to the hearing. (Photo by Alex Jurkuta/Pittsburgh’s Public Source)

Nearly 100 people signed up to praise or pan “IZ,” which would require some affordable housing in new residential developments of 20 units or more citywide.

“Pittsburgh’s Public Source is an independent nonprofit newsroom serving the Pittsburgh region. Sign up for our free newsletters.”

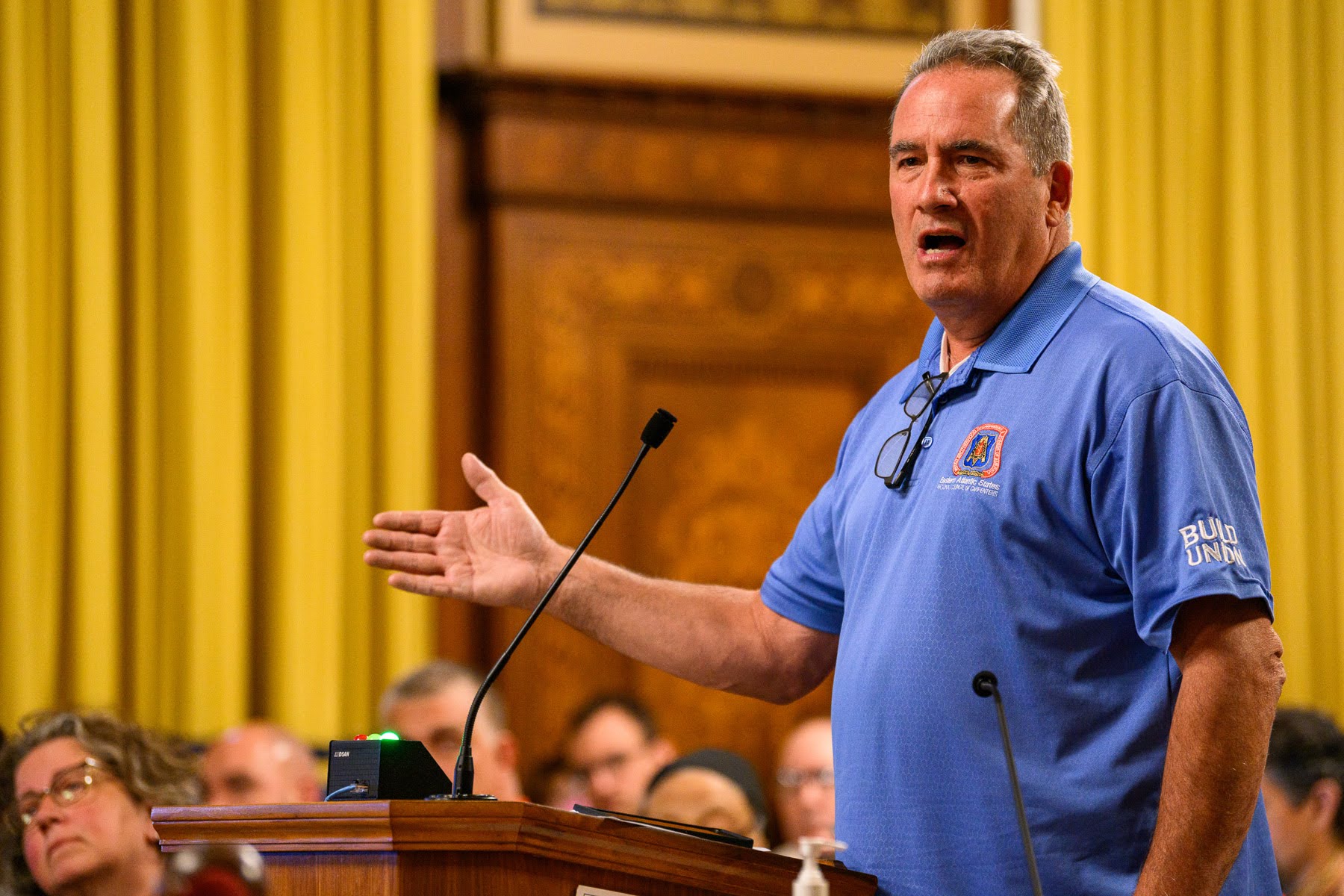

The hearing drew 70 speakers — 97 had signed up to testify — who debated Gainey’s proposal to extend inclusionary zoning [IZ] from four pilot neighborhoods to all of Pittsburgh.

Council Chambers reached near standing-room capacity, with tensions high between housing advocates and development interests. The hearing saw 40 speakers testifying in favor of Gainey’s proposal and 30 in opposition.

Before the hearing, the Housing Justice Table led a rally outside the City-County Building with roughly 25 attendees chanting “Housing is a human right,” setting the tone for hours of passionate testimony inside.

Planning Department staff told council the policy’s roots are the 2015 Affordable Housing Task Force recommendations and the 2022 Housing Needs Assessment, which documented the shortage of units and rising median rents that increasingly burden longtime residents.

In public testimony, Chris Rosselot, policy director for the Pittsburgh Community Reinvestment Group [PCRG], said the city is “in a housing crisis. … Pittsburgh lost 10,000 Black residents this decade.”

Chris Beam, a Bloomfield resident, countered that while inclusionary zoning was “well-intentioned,” it amounted to “a tax on new housing.”

IZ by the numbers

- 4 neighborhoods currently covered

- 90 neighborhoods would be covered, except parts of Downtown

- 20 minimum number of new units in a development would trigger IZ requirement

- 10% required affordable units in covered developments

- 50% of area median income is the most a household can earn to qualify for affordable units ($37,600 for an individual)

- 35 years units must remain affordable

He argued: “The best way to get affordable housing is to build more housing. We need smart, pro-growth policy.”

Construction workers warned the zoning proposal would hurt building trades, and representatives from Pro-Housing Pittsburgh, which argues for removing “burdensome restrictions,” called inclusionary zoning an “abject failure.”

Inclusionary zoning advocates argued it was essential for desegregation and that uniform rules would make development more attractive. They pointed to the City Planning Commission’s positive recommendation on January 28 as validation of the approach.

Councilors Warwick and Coghill clashed after public testimony, offering a preview of the council debate to come.

Warwick, of Greenfield, argued that inclusionary zoning would help members of the building trades afford housing in the neighborhoods in which they work, like Hazelwood, which is in her district.

Coghill, of Beechview, warned that the policy might slow development in his South Hills district, echoing concerns raised by multiple speakers about the economic feasibility of projects under the new requirements.

IZ’s long road may end

What started as an 18-month pilot program in Lawrenceville in 2019 has grown into a cornerstone of Gainey’s housing strategy, so far surviving legal challenges and expanding to three additional neighborhoods.

The pilot was made permanent in 2021, then expanded to Bloomfield, Polish Hill and most of Oakland. Last September, Gainey announced his push for citywide expansion. City Councilor Bob Charland introduced a competing version, in which neighborhoods could opt into inclusionary zoning.

The Planning Commission endorsed citywide expansion in January after an 11-hour meeting that drew around 100 speakers. The commission recommended against Charland’s version, and council killed it in July.

The path forward for Gainey’s inclusionary zoning proposals depends on several council members who control the legislative calendar.

IZ timeline

- 2019 Pilot begins in Lawrenceville

2021 Made permanent

2022 Expanded to Bloomfield, Polish Hill

2023 Oakland added

2024 Gainey proposes citywide expansion and Charland introduces alternative

2025 Planning Commission endorses Gainey IZ, council defeats Charland’s bill

Following Wednesday’s public hearing, either Council President Daniel Lavelle, Land Use and Economic Development Committee Chair Bobby Wilson, or the bill’s sponsor Deb Gross can bring the legislation to the table for discussion and potential amendments.

Councilor Erika Strassburger indicated the proposal could come up next week for discussion, amendments and a potential preliminary vote, which could be followed by a final vote the following week.

Several factors could extend the process.

The proposals also face ongoing legal uncertainty, as the Builders Association of Metropolitan Pittsburgh has sued the city over the existing, four-neighborhood inclusionary zoning requirements, arguing they constitute an illegal taking of property. Even if council approves the expansion, the policy’s future could be decided in court.

IZ effects so far debated

Six years of inclusionary zoning in Lawrenceville have both sides claiming the data supports their take.

David Vatz, representing Pro-Housing Pittsburgh, cited their study showing construction dropped 30% in Lawrenceville after the policy took effect. “We spent months studying it, and we looked into how many [affordable] units have been created by the program. It’s not many. It’s less than 40 units,” he said.

Advocates argue this misses the point. “If you want to measure the effect of IZ, it makes sense to measure it at the moment it’s actually applied — when you file for your zoning application,” explained Dave Breingan, executive director of Lawrenceville United, who co-authored a report defending the policy. Large projects typically take 2-3 years from approval to occupancy, meaning a 5-year-old policy only shows 2 years of completions.

Andrea Boykowycz, executive director of Oakland Planning and Development Corp., added that there are projects currently under construction that trigger inclusionary zoning: “Walnut Capital is building the Caroline and McKee Place … When it is complete, it’ll deliver 16 affordable units out of a total of 159.”

She listed five developments in Oakland’s pipeline that would create more than 100 affordable units, arguing “that’s more projects than for the equivalent period of time before inclusionary zoning was put in place.”

City Controller Rachael Heisler has cautioned in a memo to council that neither side had definitive proof of inclusionary zoning’s effects due to limited data.

At the hearing, Emma Gamble, a community organizer from Lawrenceville United, said research shows inclusionary zoning helps prevent displacement of low-income residents. She testified that “data cited in this hearing has been largely debunked” by Heisler’s report.

Effect on financing could be key

In an interview with Public Source before the hearing, Charland offered a technical explanation for why projects might stall under inclusionary zoning.

Charland noted that banks won’t lend unless projected returns on investment meet certain thresholds that, he said, can’t be achieved under inclusionary zoning. “I know very well there are a lot of projects on the list that are entitled [to proceed] that you’re not going to see a shovel in the ground” because the financing won’t work.

Boykowycz said development decisions depend on many factors, listing soil conditions, parcel sizes, transportation access and financing availability as variables the economic models ignore.

Less segregation, or less housing?

Advocates for inclusionary zoning also framed it as anti-segregation policy.

“It ensures people from low-income families have an actual opportunity to live in thriving neighborhoods,” said Druta Bhatt, PCRG research analyst and a co-author of PCRG’s research on IZ. “Research shows this access correlates with intergenerational wealth building through better schools, healthcare, and social networks.”

This distinguishes inclusionary zoning from Housing Choice Vouchers, which theoretically offer similar mobility but have had challenges securing buy-in from landlords. IZ creates affordable units in hot neighborhoods by requirement, not choice, she said.

But opponents warn the policy could backfire. “Simply put, we will lose a lot of new housing if IZ passes,” said Pro-Housing Pittsburgh’s Vatz. “Home builders will start to look elsewhere and build elsewhere, in places like the Pittsburgh suburbs, or cities like Columbus, Cincinnati, Cleveland.”

He argued that “renters across the income spectrum pay for IZ through higher rents, which are driven higher still by reducing the number of new homes being built.”

For Breingan, who’s spent a decade fighting for inclusionary zoning, the slow pace is frustrating. “Some arguments are like, we’re moving too fast on this. Ten years is not a fast amount of time” he told Public Source.

He sees developer influence as the key obstacle: “Developers and the real estate industry have a lot of influence in the city. … The concerns that have stalled this thing are extremely over-inflated and are less rooted in objective reality than power.”

Does IZ have the votes?

Gainey’s proposal needs five council votes to pass.

Advocates of inclusionary zoning focused on Strassburger, of Squirrel Hill. “Council member Strassburger has made comments on the public record saying that she will work on IZ,” said Maddy McGrady, co-chair of the Housing Justice Table. “Wednesday is that moment, that time has come.”

Strassburger told Public Source that she’s concerned about whether projects will secure financing.

“If a program is going to succeed, particularly right now, where it’s as challenging to build housing as it ever has been … it has to be funded,” Strassburger said, signaling she’s working on amendments to address financing gaps that might stem from inclusionary zoning.

She said her past statements don’t guarantee a yes vote without amendments.

Correction (9/11): Chris Beam’s name was misspelled in an earlier version of this story.

Brian Nuckols is an investigative journalist based in Pittsburgh. His reporting focuses on U.S. politics, local government and technology, with a particular interest in how powerful institutions shape the lives of vulnerable communities. His work has appeared in The Lever, PublicSource, Jacobin and Pirate Wires. He can be reached at brianjnuckols@gmail.com or on X at @briannuckols13.

This article first appeared on Pittsburgh’s Public Source and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.![]()