Lou Davis, 67, of Larimer, shares thoughts about his former neighbor, Alice Lanntair, at a memorial to her at Rodman Street Missionary Baptist Church, Thursday, May 15, 2025, in East Liberty. Davis and Lanntair would talk in the halls at Harriet Tubman Terrace. At right, Tina Calabro, of Highland Park, who organized the event for her friend. (Photo by Stephanie Strasburg/PublicSource)

Half of Pittsburgh-area seniors live alone, and with isolation and government cuts come higher risks of fatal accidents and emergencies.

“PublicSource is an independent nonprofit newsroom serving the Pittsburgh region. Sign up for our free newsletters.”

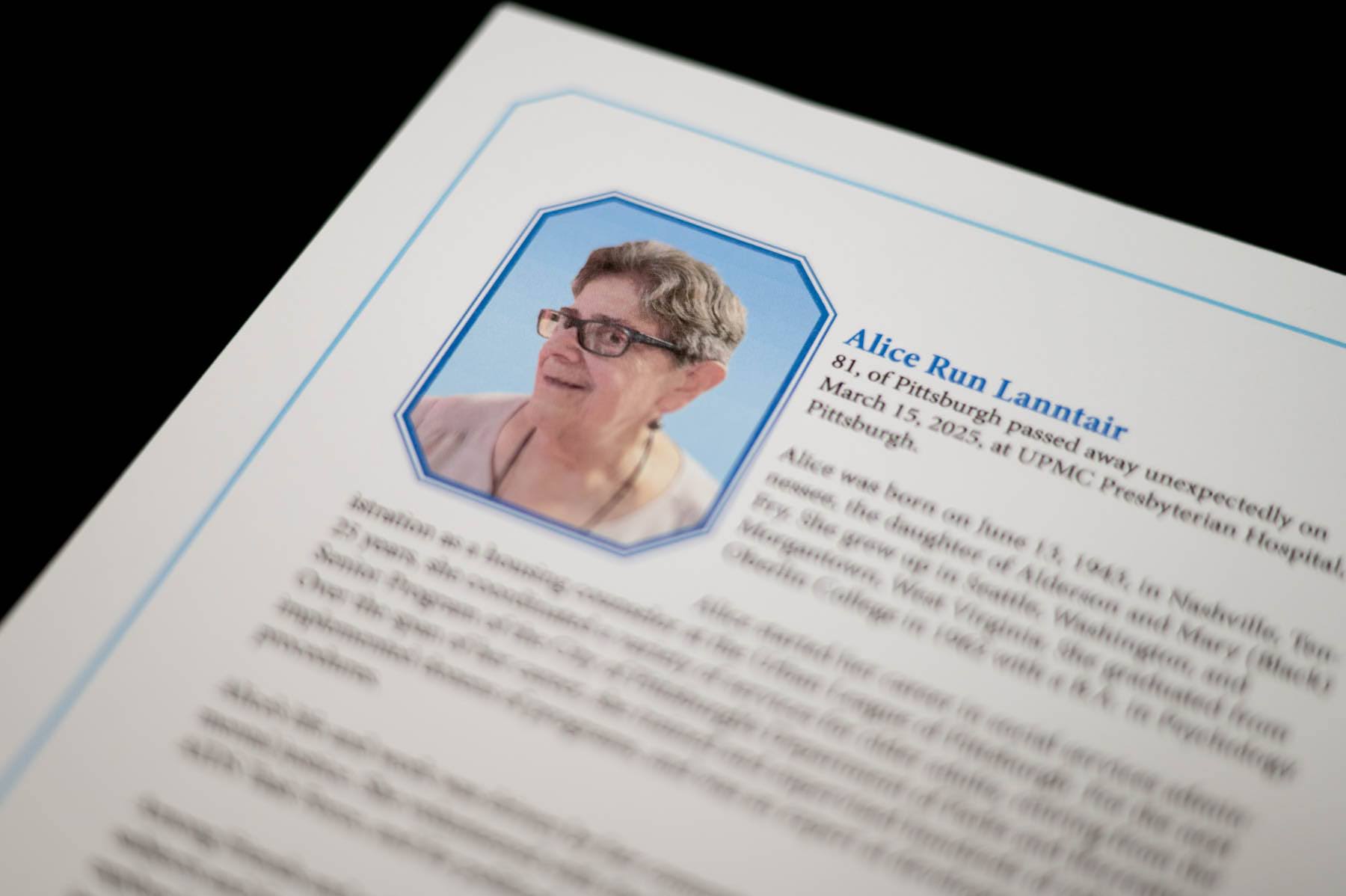

Around March 10, Alice Lanntair, 81, fell down between the bedroom and living room of her apartment at Harriet Tubman Terrace in Larimer.

Because she did not press the 911 button on the pendant she usually wore, packages piled up outside her door, and neighbors did not notice her taking her customary strolls in the hall.

An employee making a wellness check on March 14 found her barely breathing. She was taken to UPMC Presbyterian and died the next day. She had lain three to four days without food or water on the cold linoleum floor.

Lanntair’s passing followed the deaths of actor Gene Hackman and his wife in New Mexico — grim reminders, advocates for senior citizens say, of the need for older adults and their caretakers to update plans for independent living. “The more I learned about the situation, the more it got me thinking just how important it is that we’re all prepared, either for our loved ones, our caregivers or even ourselves,” said Amanda Krisher, associate director for behavioral health at the National Council on Aging in Arlington, Virginia. “We need backup plans. We don’t know when something like this could happen.”

The welfare of senior citizens may be further jeopardized by moves in Washington, some driven by the Elon Musk-inspired Department of Government Efficiency. In March, budget cutters laid off or forced out 20,000 employees in the Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], including the Administration for Community Living [ACL]. That agency has overseen some Meals on Wheels programs, which are partially federally funded and deliver food and conduct welfare checks on older adults, creating concerns about its fate.

Seniors concerned about probing cameras

Taking care of older residents is especially important in Allegheny County. With nearly 20 percent of its population 65 and older, the county ranks second in age among the 40 largest in the country, according to the University of Pittsburgh’s Center for Social and Urban Research. Among nearly 334,000 residents 60 and older in the county, a 2023 survey for the U.S.Census Bureau found that 48 percent live alone.

Abigail Gardner, spokeswoman for the Allegheny County Medical Examiner’s Office, estimated about 100 persons at least 65 years old died at home last year. Of those, dozens passed away alone.

Such deaths occur in spite of the region’s health care capacity and the ubiquity of connecting technology.

“As a society, we’ve done a great job figuring out how to help people live longer, but we’ve come up short on how to help people live well,” Pamela E. Toto, director of Pitt’s Healthy Home Laboratory and a professor in the Department of Occupational Therapy, wrote in an email. “We need new strategies that enable older adults to maintain their independence and safety. Those solutions, which include technology and environmental modifications, exist! And they work!”

The Oakland lab focuses on helping older people live safely and comfortably in their own home, and helping older partners evaluate the house and its furnishings. “We’re trying to improve the way people age in place,” said Toto.

A detection light in the lab’s living room monitors for potential falls, triggering an Alexa-like speaker that asks if someone has fallen. If so, the device notifies that person’s emergency contact. Pitt’s team also extended a swivel bar to the 10-foot-4-inch ceiling. That eases sitting down and getting up from an easy chair.

There’s no innovation or technology that would work to protect every isolated senior from danger. Even wealth and fame aren’t failsafes.

Hackman, 95, died around Feb. 18, and Betsy Arakwawa, 65, his wife and caretaker, about Feb. 12, but their bodies were not discovered in their home until Feb. 26.

Agencies weigh safety, privacy

Representatives of the city and county housing authorities said they rely on neighbors, tenant councils and social service agencies to monitor senior citizens in independent living. But housing employees are reluctant to enter the apartments. They are concerned that “you can infringe on someone’s privacy and they don’t want you,” said Michelle Sandidge, chief community affairs officer for the Housing Authority of the City of Pittsburgh.

Rich Stephenson, acting executive director of the Allegheny Housing Authority, said deaths like those of Hackman and Arakwawa reinforced the importance of getting inside the apartment.

When do his employees make a wellness visit?

“Unfortunately, when you miss paying your rent, then we go [inside],” Stephenson said. “I’m ashamed to say it.”

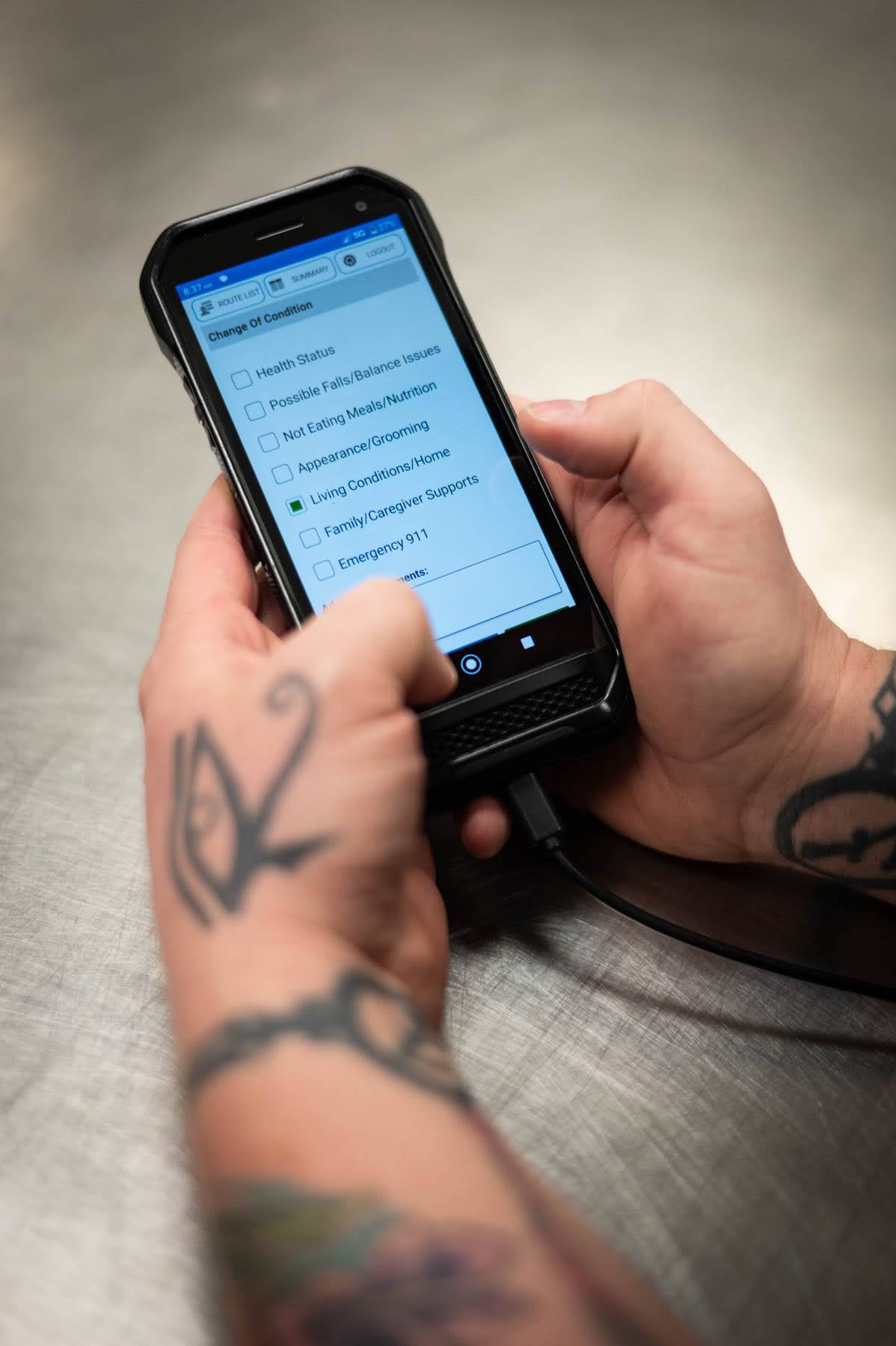

The Allegheny County Area Agency on Aging communicates with about 50,000 consumers through texts, landline calls or emails in nearly 20 languages and, if requested, provides free emergency pendants.

Many officials said senior citizens dislike monitoring by technology, particularly cameras. Stephenson suggested a camera in his mother’s home. She refused.

Meals and a smile — for now

Meals on Wheels serves 251 million meals to more than 2 million Americans a year, including 9 million meals to 100,000 Pennsylvanians. The public-private partnership also provides a friendly visit and safety checks on recipients and their homes.

On a recent Wednesday, Dave Veseleny delivered meals to about 100 people in the Homestead area. In his seven years with the program, he has made three 911 calls. Two years ago, he found a lady lying on the floor from a fall 16 hours before. “It’s a good thing I been there because she probably would have bled to death,” he said.

Other Meals on Wheels drivers have found bodies.

Veseleny stopped at Homestead Apartments and announced his presence with his signature musical knock. Loretta Walker called him in. She sat barefooted in a pink bathrobe on a gray chair in the living room. A television set droned a morning talk show on a stand enshrining a framed photo of her son James, one of her two children. He drowned in 1978 while fishing in the Allegheny River. He was just 10.

Veseleny comes three times a week. On this day he brought a meal of rosemary chicken, white bread, whipped potatoes, Brussels sprouts and mandarin oranges, and another of a chili hot dog with bun, green beans and fresh fruit.

Flashing a smile, Walker bantered with Veseleny and some visitors. “I can’t go to the bathroom without taking this with me,” she said, rolling the walker beside her chair. The 79-year-old woman recited a litany of medical issues — diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, osteoporosis, a knee replacement — that would make cooking on her stove hazardous.

Despite her walker, she has fallen three or four times. After one tumble, she lay on the floor overnight until paramedics, alerted by her granddaughter, helped her into her chair.

In a news release dated March 27, HHS Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. announced that cuts would save $1.8 billion a year. “This department will do more — a lot more — at a lower cost to the taxpayer,” Kennedy wrote.

Some in the care sector worry that the department will do less, including via its Administration for Community Living.

“I’m concerned with the elimination of ACL we’re going to see more people forced to have no choice — to enter nursing homes rather than stay in their own homes, which is what they want to do,” said Alison Barkoff, a health law and policy professor at George Washington University. She ran ACL in the Biden administration.

If President Donald Trump stalls Meals on Wheels, Walker is uncertain what she would do. “I don’t know, I’d probably be in Dutch putting something together, and the smoke alarm would go off,” she said.

Walker added wryly, “I could have Elon Musk come over and deliver something for me.”

An elder orphan

Alice Lanntair was born in 1943 in Tennessee and grew up in Seattle and Morgantown, West Virginia. Lanntair worked as a housing counselor and later on various city programs for seniors, including Meals on Wheels.

Divorced, with a cat but no family, Lanntair called herself an “elder orphan.” Her hippy-length hair shortened to a salt-and-pepper bob, and she thought deeply about the environment and justice. “She was feisty. She talked a lot, I mean a lot. She said what she meant,” said Gwen Sewell, service coordinator of privately managed Harriet Tubman Terrace.

Lanntair walked all four floors of the building with her brown wooden cane, and later, frail and stooped, a purple walker. But that did not curb her independent streak, said Tina Calabro, of Highland Park, who met Lanntair through a women’s center and support group, then became the elder woman’s friend and executor.

“A guy at a crosswalk got out of his truck to help her cross a street, and she waved him away and said, ‘I don’t need help,’” Calabro recounted.

Although the building is for independent living, Sewell said, “If I don’t see the person in a while, I’ll knock on her door. We don’t have to go in and check on anybody, but we do.”

Lanntair, however, died of sepsis, an extreme reaction to an infection, presumably caused by wounds from a fall.

Remembering Alice

The May memorial took place in the basement of Rodman Street Missionary Baptist Church, near Lanntair’s apartment. Sixteen neighbors and friends gathered at tables decorated by a glass vase of artificial white roses and purple butterflies atop a black tablecloth.

Photos of Lanntair’s life flashed on a screen — her as a child, a young lady hunched on a boulder, a graduate in a gown. The mourners shared recollections. Her neighbor Velda Tomblin, 67, recalled falling in the shower and screaming. Lanntair, on one of her walks, alerted Tomblin’s friend, and he called paramedics.

“If it wasn’t for her walking the halls, I don’t know,” she said, laughing, “I might not be here.”

Lou Davis, 67, boasted of being the only terrace resident invited inside Lanntair’s home. He later made a somber observation. “I see a lot of loneliness in the apartments,” he said. As grandchildren get older, visits to grandparents get rarer.

“I think it’s important that we check on each other,” he said. “If we had done that with Miss Alice…”

His voice trailed off.

Bill Zlatos is a freelance writer in Ross and can be reached at billzlatos@gmail.com.

This story was fact-checked by Rich Lord.

This article first appeared on PublicSource and is republished here under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.