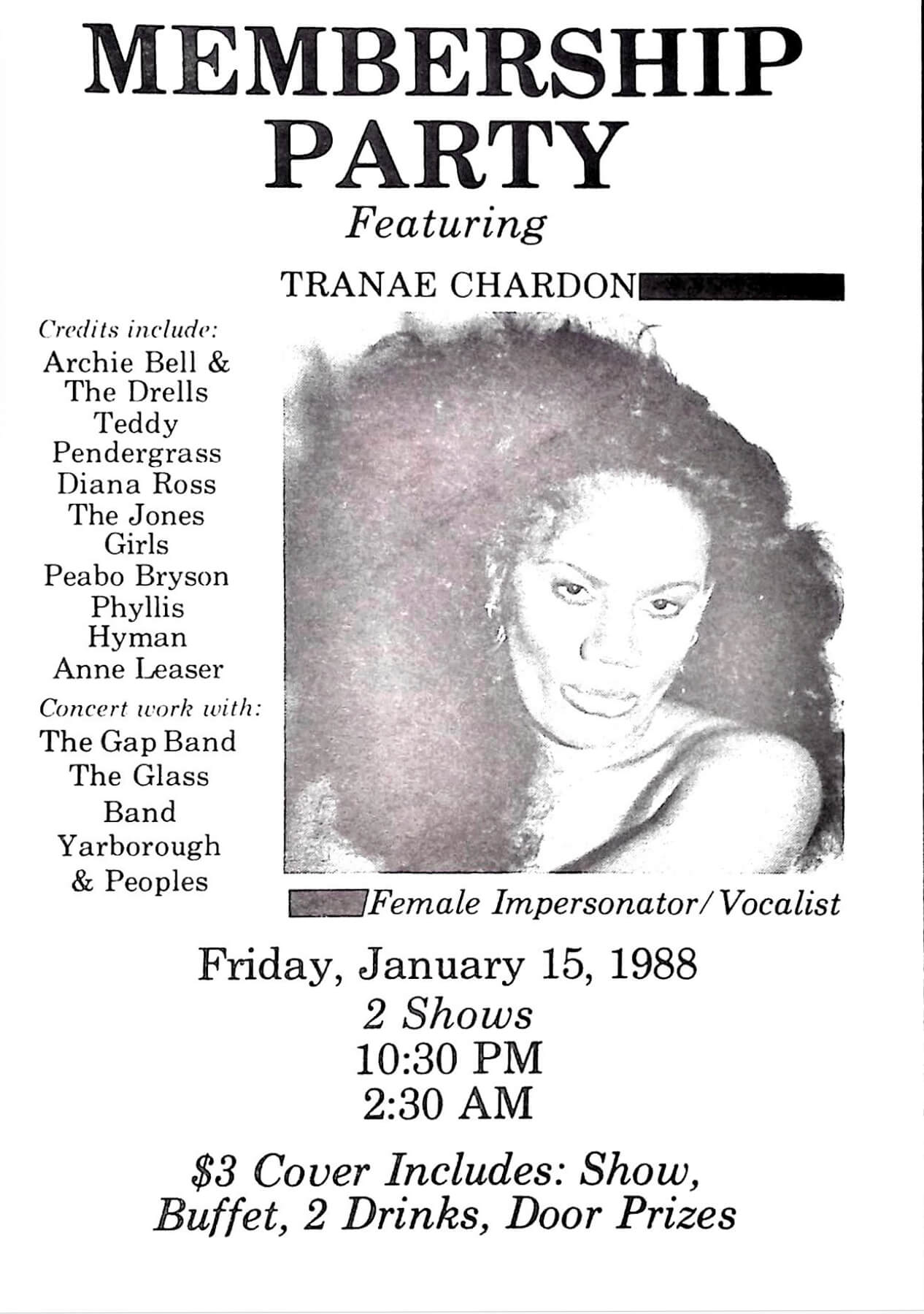

From left, punch membership rebate card for Norreh Social Club, portrait of gay bar owner Robert “Lucky” Johns, pictured left, with Donny’s Place namesake Donald Thinnes, center, and exterior of 1226 Herron Ave. in Polish Hill, formerly Donny’s Place. (Photos courtesy of Donald Thinnes Collection, Heinz History Center Detre Library and Archives/Illustration by PublicSource)

Efforts to preserve the shuttered Donny’s Place in Polish Hill, without the support of the property owners, go to the Pittsburgh Historic Review Commission in a process set to start Feb. 5.

“PublicSource is an independent nonprofit newsroom serving the Pittsburgh region. Sign up for our free newsletters.”

A group of LGBTQ community activists and Polish Hill residents have nominated the former Donny’s Place bar on Herron Avenue for recognition as the first historic landmark in Western Pennsylvania designated specifically for ties to LGBTQ history. Between 1973 and 2022, Donny’s Place was a hub for queer culture and an important public health outreach center during the early days of the HIV/AIDS crisis, though obstacles remain for the City of Pittsburgh Historic Site designation effort.

The building Donald Thinnes owned until he died last January isn’t a grand Victorian mansion, an Art Deco masterpiece or a tavern where George Washington allegedly slept. The former bar is a two-story brick commercial building that occupies a 2,870-square-foot lot in a 2.23-acre area where a developer wants to build 19 townhouses. It’s a place where a lot of Pittsburgh history was made, according to the people backing the landmark nomination.

But the property also is valuable real estate that occupies part of a larger area that a 2017 Urban Land Institute study says is primed for transit-oriented development.

The nominators face an uphill battle with several obstacles in their way, not the least of which is convincing the Historic Review Commission [HRC], City Planning Commission and City Council that the building’s history should outweigh its apparent lack of architectural distinction. They also need to overcome council’s decadeslong tendency not to designate historic sites without owner support.

“Donny’s Place was not just kind of a center for Pittsburgh gay life, but was really like a convergence point,” said writer Dade Lemanski, who researched and wrote the nomination submitted to the city in October.

The bar played a life-changing role in Pittsburgh and regional history. “The number of people and lives that passed through Donny’s Place and were transformed by it and transformed in it, there just really is no other place like it and no other place for many hundreds of miles to go to encounter that kind of history,” said Lemanski.

An ordinary looking building with an extraordinary story

No one remembers who constructed the building at 1226 Herron Ave. and there don’t appear to be any surviving records. Joseph C. Dawson, an Irish saloonkeeper, bought it in 1917. Two years later, help wanted ads in local newspapers described the property as a “new apartment building.”

It was one of three buildings on the east side of Herron Avenue just before the bridge over what is now the East Busway. Each had restaurants and saloons on their ground floors and apartments above. Until Thinnes consolidated the properties at 1226-1230 Herron Ave., different individuals owned and operated the establishments.

Newspaper archives paint a colorful picture of the activities that took place in the three Herron Avenue buildings. There were multiple raids for bootlegging and gambling in the 1920s and 1930s. The saloons and restaurants in the building where Donny’s Place was founded had several names over the years: the Union Hotel, Porter’s Restaurant and the Norreh Social Club.

Over the years, the Herron Avenue bar transitioned from an Irish saloon into a social club partly owned by an Italian American family whose members included the owners of a popular Strip District restaurant and John Fiorucci, a former boxer, bootlegger and gambler turned city alderman and police magistrate.

In October 1973, Thinnes began operating the Norreh Social Club after a police raid earlier that year landed the previous proprietor, Helen Caruso, in jail on gambling charges. The following year, Thinnes’ parents bought the property. They sold it to their son in 1979.

The club’s name, noted CMU historian Harrison Apple, is Herron spelled backwards. Apple wrote their 2021 University of Arizona Ph.D. dissertation on the history of Pittsburgh gay bars and they are a founder of the Pittsburgh Queer History Project.

In the 1940s and 1950s, the lower stretch of Herron Avenue was still considered part of the Upper Hill District’s Herron Hill neighborhood. “I was born in Herron Hill and still live in the neighborhood (now at 1228 Herron Ave.),” John Fiorucci told the Pittsburgh Press in 1947 after then-Mayor David L. Lawrence appointed him as a police magistrate.

Thinnes was a lifelong Pittsburgh resident. Born in 1947, Thinnes grew up in Bloomfield. He served a tour of duty in Vietnam between 1966 and 1968. After returning to the city, Thinnes went to work for Robert “Lucky” Johns. “Lucky was a fixture in Pittsburgh gay history,” said CMU historian Tim Haggerty. Lucky operated Pittsburgh’s earliest openly gay bars and he trained generations of newcomers, like Thinnes, in the hospitality trade.

Thinnes began working in one of Lucky’s bars as a janitor, said Apple. Thinnes was a quick study and within five years he struck out on his own and took over the Norreh Social Club. “He was modeling it off of what he had learned from Lucky,” Apple said. “Lots of bars within one place and people sort of territorialized them. So that if you were looking for something, you could find it.”

Drawing on what he learned from Lucky, Thinnes carved up the space inside his buildings into specialized areas catering to multiple segments of Pittsburgh’s LGBTQ community, including a bar for lesbians and space for the leather crowd.

While still operating as the Norreh Social Club (Thinnes changed the bar’s name in 1991 to Donny’s Place), Thinnes began collaborating with the Pitt Men’s Study and other public health organizations battling HIV/AIDS. The popular hub for LGBTQ entertainment that offered spaghetti dinners, drag shows and contests became a key site where gay men learned to protect themselves against the disease and where scientists collected data to fight it.

Historic designation rare for LGBTQ landmarks

Polish Hill residents Lizzie Anderson and Matthew Cotter completed and filed the landmark nomination, with technical support from Preservation Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh’s historic preservation law requires that all designated sites meet at least one of 10 criteria related to architectural significance or a building’s ties to important people and events. The Donny’s Place nomination says that the building meets four criteria for historic designation:

- Ties to important people (Thinnes)

- Important cultural and social aspects (LGBTQ culture and public health)

- Connections to important historical themes

- As a “familiar visual feature.”

If the former Donny’s Place is designated historic, it will be the only officially recognized LGBTQ historic site in Western Pennsylvania. There are 191,681 sites in a Pennsylvania State Historic Preservation Office database of documented historic sites in the state, though only 10 are specifically associated with LGBTQ history.

There are very few LGBTQ sites represented in the National Register of Historic Places. In 2023, only 30 of more than 96,000 properties were listed because of their ties to LGBTQ history. “It’s certainly not representative” of the importance of LGBTQ history in America, said historian Susan Ferentinos. Ferentinos wrote the 2014 book, “Interpreting LGBT History at Museums and Historic Sites,” and contributed a chapter in the 2016 National Park Service study, “LGBTQ America: A Theme Study of Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer History.”

Pittsburgh has a long history of gay gathering places in marginalized communities like the Hill District where non-queer bar owners welcomed members of the LGBTQ community. Acclaimed photographer Teenie Harris captured some of them in his many decades documenting Hill District culture.

One thing that distinguishes Donny’s Place is its longevity: It remained open as a gay bar for almost 50 years, the longest run in the city. Lucky’s in the Strip District is another bar with a long history that’s still open. So is Brewers, a Lawrenceville bar that almost closed but was sold last year.

Many LGBTQ-oriented bars, however, have closed. Pegasus operated between 1980 and 2009 in a Liberty Avenue space that earlier housed the Copa, a Jewish mob-run nightclub. The Pittsburgh Eagle, open from 1994 to 2012 on the North Side, was another. Scott Noxon, who helped Donny’s Place recover after the COVID lockdowns, owned Pegasus and the Pittsburgh Eagle.

Pittsburgh’s LGBTQ-oriented bars aren’t architectural gems like some counterparts in the non-queer world. Donny’s Place is an ordinary-looking commercial building with graffiti tags, peeling painted signs and boarded up windows.

For a gay bar, though, evidence of neglect and disinvestment can contribute to historical significance. “They were marginalized spaces to begin with. They were under-resourced and they’re often in neighborhoods that reflect that as well,” Ferentinos said of many gay bars. “They’re not the grand mansions on the hill.”

“Some of the architectural significance of gay bars of that period is that they’re pretty low profile because it wasn’t necessarily safe to be out,” said Lemanski. “The anonymity is part of its architectural significance.”

Not everyone supports making Donny’s Place a historic site

It’s the lack of architectural distinction that people who oppose designating Donny’s Place as a historic site frequently cite. David Vatz is a community activist who frequently comments on development activities in the city. He’s part of Pro-Housing Pittsburgh, a group that advocates for building more housing. Vatz finds little architectural merit in the former Donny’s Place building.

“I think anybody can look at that Donny’s building and know that it has absolutely no relevance from an architectural standpoint and should not be preserved,” Vatz said.

Within hours of a Dec. 16 development activities meeting [DAM], Vatz posted on Bluesky, “Originally a 30-townhome development, now planned as a 19-townhome development in Polish Hill (downsized to avoid IZ [inclusionary zoning]). Now the neighborhood is trying to kill it all together with a bad-faith historic designation for this building.”

Vatz later clarified that he believed the designation effort was “an attempt by the community to block a development in their area.”

The Polish Hill Civic Association is the city’s registered community organization [RCO] for Polish Hill and it organized the December DAM where residents and other stakeholders expressed diverse opinions. The community group has discussed the historic site nomination at its board meetings, but hasn’t taken a position on it.

“We decided that we wouldn’t really take a role outside of being the neighborhood RCO,” said Polish Hill Civic Association President Colleen Shuda. A big factor in the organization not taking sides is the lack of support by the property owner, Thinnes’s estate.

Thinnes named a real estate agent as his executor. PublicSource reached out to the executor and the law firm handling Thinnes’s estate, but neither responded to emails and voicemails.

Vatz and Pro-Housing Pittsburgh are the only parties to emerge thus far as opponents to the designation.

The legal realities

In 2019, Thinnes signed a contract to sell his property to Laurel Communities for $1,050,000. Laurel Communities did not respond to an interview request.

Laurel Communities in 2020 proposed building 27 townhomes at the corner of Herron Avenue and Ruthven Street. In 2023, the developer cut the number to 19 in response to opposition. “That all then led to them revising their plans in order to bypass another zoning hearing and also to not have to have any affordable units by building 19,” said Anderson. City inclusionary zoning rules, in place for Polish Hill and a handful of other neighborhoods, kick in when a new development’s unit count hits 20.

The former Donny’s Place bar is about 200 feet from the East Busway’s Herron Station. In 2017, the Urban Land Institute recommended rezoning the area where the former bar is located. The Planning Commission was supposed to vote on the changes in December, along with zoning changes in other parts of the city. That vote was postponed and the commission could take it up again next month, according to city planner Andrew Dash.

Though the people who support designating the former Donny’s Place as historic believe they have a strong case, they need to navigate multiple hearings and the court of public opinion to get there, starting with the Historic Review Commission process.

Though Pittsburgh’s historic preservation law doesn’t require property owner consent, the council rarely approves a historic designation proposal without it.

Designation typically prevents demolition and it imposes regulatory burdens on property owners who must get HRC approval for most changes to the building’s exterior. If the preservationists are successful, they’ve pledged to firm up plans for the building — a property that they don’t own and as private citizens would wield little power over other than having a say in future HRC hearings about proposed changes.

The preservationists have discussed possible new uses for the building, including a museum and affordable housing for aging members of the LGBTQ community. “So who knows exactly what is possible,” Anderson said in the DAM. Anderson would like to see a use “that continues to honor the history on that site.”

Alternatives to historic designation

“I’m sure that the people do believe in the significance of this bar,” Vatz said. “You can honor the significance of a place like that in many ways other than preserving an unremarkable building.”

Opponents to landmarking buildings often suggest erecting historic markers instead of historic designation.

Advocates for saving the property said that’s not enough. “There are so many things that can be understood by being experienced and felt that are not possible to convey in a marker,” said Lemanski.

Historian Ferentinos has a similar view. “I am not as opposed to historical markers as some public historians are,” Ferentinos said. “But the idea that that would be equivalent, I must say I personally find troubling because it’s important that that’s not a beautiful building. That’s part of the story, that’s essential to the story and to understanding LGBTQ history and all history.”

The former Donny’s Place’s fate will be decided later this year. The HRC will determine Feb. 5 if the nomination is viable and a hearing will be held — likely in March, according to preservation advocates — to vote on whether to recommend the designation to council. After that, the Planning Commission will weigh in with its recommendation. The council will have 120 days from the date the commission submits its recommendation to make a final decision.

David Rotenstein is a Pittsburgh based writer and historian and can be reached at david.rotenstein@gmail.com.

This story was fact-checked by Livia Daggett.

This article first appeared on PublicSource and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

PARSELY = { autotrack: false, onload: function() { PARSELY.beacon.trackPageView({ url: “https://www.publicsource.org/pittsburgh-queer-history-landmark-preservation-review-commission-lgbtq-activists/”, urlref: window.location.href }); } }